By Tano “Likalik” M. Emboc

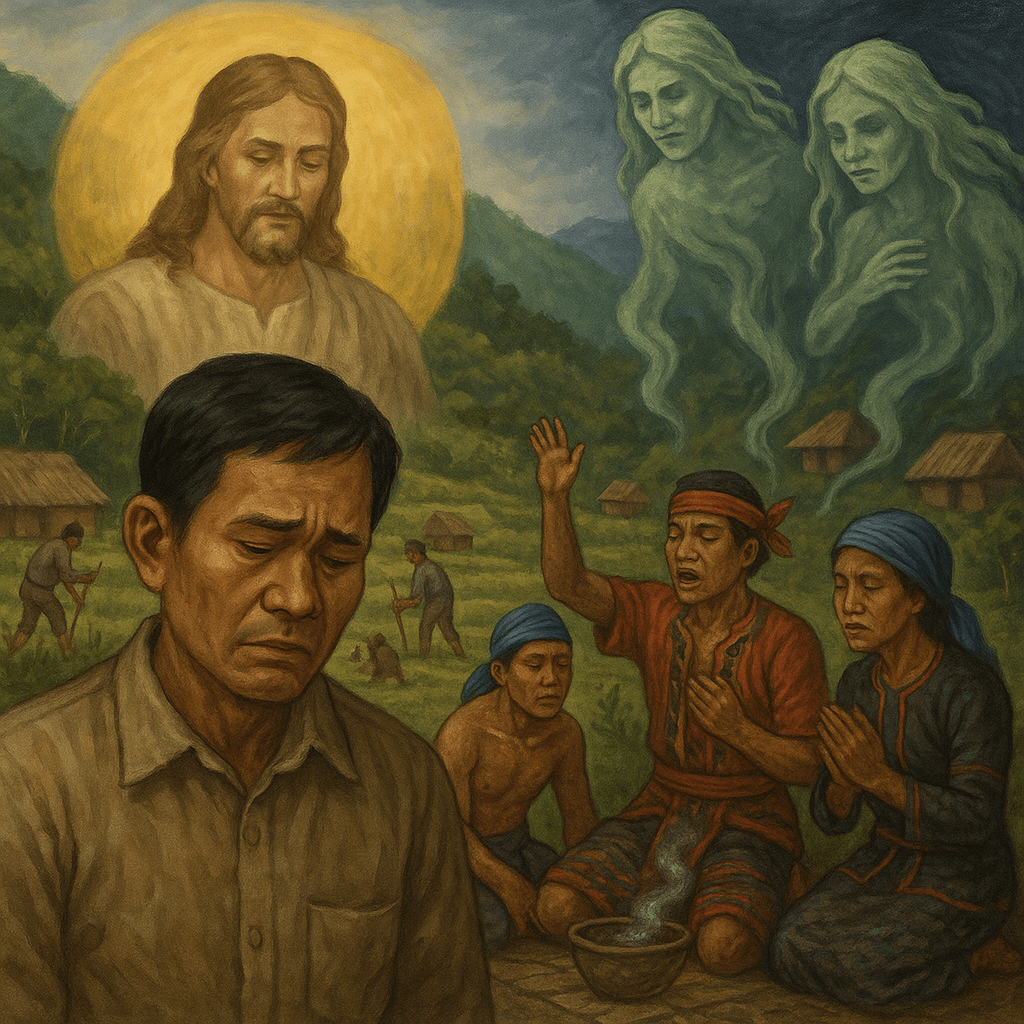

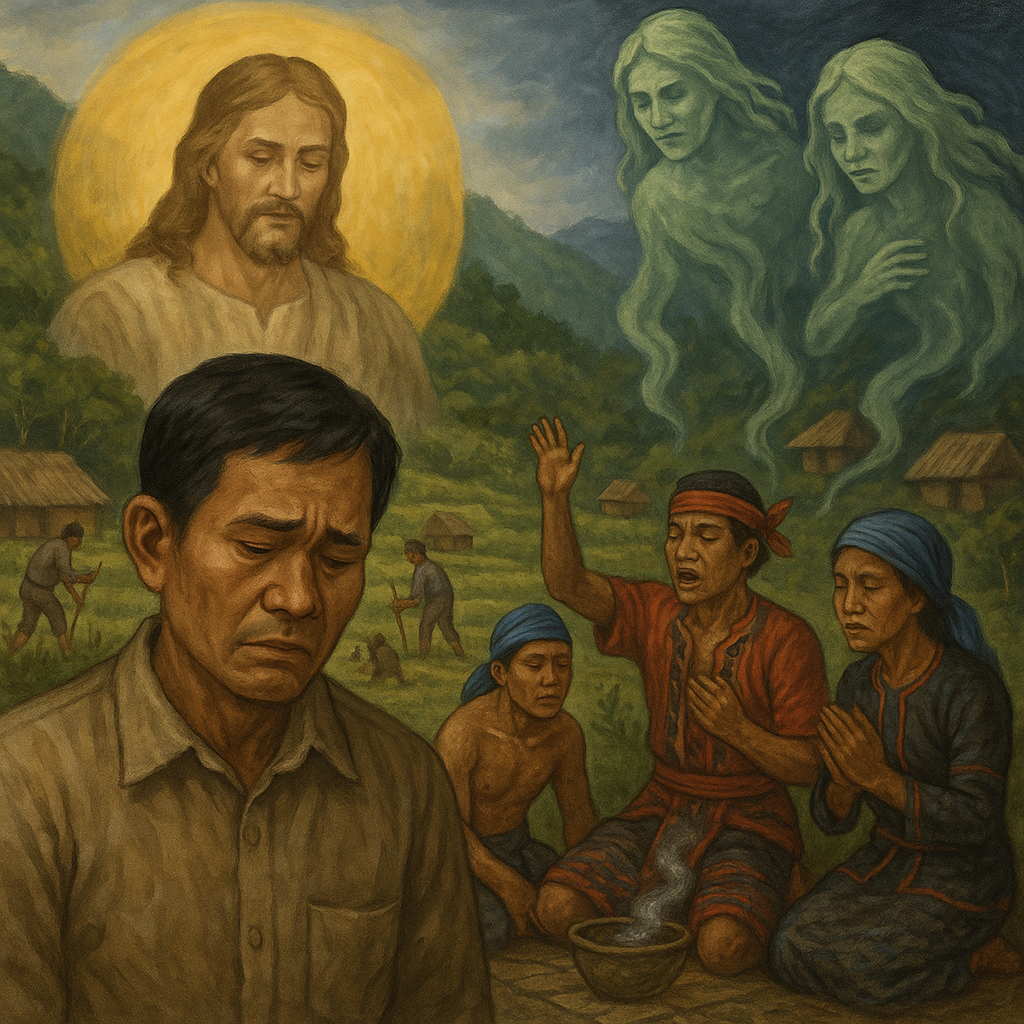

The problem: Excluded middle

Most of the Manobo pastors who have limited education are falling away, leaving the ministrysince they cannot cope up with or were not trained appropriately how to deal with the worldview/cosmology of the Manobo, especially with regard to the spirit world, to the unseen realm, or the excluded middle. Settled in the mountain ranges of Manobo highlands where pluralistic animism is the primary religion practiced by the ethnic tribes not just by Manobo people passed on by their ancestors since time immemorialMost of their activities such as farming, festivals, fishing and hunting, marriages, and making houses evolve around the spirit world that controls human affairs and the future of mankind. In response to their capacity Manobo asks for interventions for healing of diseases, protection from bad omen or fate, spiritual attacks and punishments, acts of witchcraft, and mortal enemies. In this light, Manobo people have a great fear of the spirits and even allow themselves to be possessed as mediums in order to communicate with the spirits and be subjected to their will. Moreover, death bridges life from being mortal to immortal and be able to join with their ancestors and the spirits in the spirit world. Thus, it makes Christianity or the necessity to believe in Christ not necessary for both the present and future life because he is distant God and has nothing to do with the domain of mankind.

Most of the Manobo pastors who have limited education are falling away, leaving the ministrysince they cannot cope up with or were not trained appropriately how to deal with the worldview/cosmology of the Manobo, especially with regard to the spirit world, to the unseen realm, or the excluded middle. Settled in the mountain ranges of Manobo highlands where pluralistic animism is the primary religion practiced by the ethnic tribes not just by Manobo people passed on by their ancestors since time immemorialMost of their activities such as farming, festivals, fishing and hunting, marriages, and making houses evolve around the spirit world that controls human affairs and the future of mankind. In response to their capacity Manobo asks for interventions for healing of diseases, protection from bad omen or fate, spiritual attacks and punishments, acts of witchcraft, and mortal enemies. In this light, Manobo people have a great fear of the spirits and even allow themselves to be possessed as mediums in order to communicate with the spirits and be subjected to their will. Moreover, death bridges life from being mortal to immortal and be able to join with their ancestors and the spirits in the spirit world. Thus, it makes Christianity or the necessity to believe in Christ not necessary for both the present and future life because he is distant God and has nothing to do with the domain of mankind.

Ethnoscopic: Cultural lens

Twelve of Mindanao’s indigenous people groups are considered Manobo, accounting for a Manobo population on Mindanao of around 400,000 and making them the largest Lumad language community indigenous to Mindanao. The most widely accepted theory on the origins of Manobo communities in the central and northern highlands of Mindanao is Richard Elkins’ “Proto-Manobo” theory. According to Mcmahon, Elkins postulates the idea that the Proto-Manobo speakers were originally a pre-Islamic Malay population that settled on the southwestern coast of Mindanao near the mouth of the Rio Grande, close to what is now Cotabato city in the province of Maguindanao. These then followed the Pulangi River east and north to the Bukidnon plateau from where the process of eventual separation into sub-groups was set in motion. The Mindanao epic known as Agyu depicts the Manobo or Bukidnon ancestors living at the coast and having to respond to the intrusion of Islam or Spanish Catholicism. The hero, Agyu, rejects both and moves to the mountains in Mindanao’s interior with his subjects. To avoid oppression from invaders they continue to move farther into the interior and become more rooted in their ancient beliefs, receiving supernatural powers from the tumanud (spirits), who help them, and eventually achieve immortality when they are lifted into the sky. (Mcmahon, 2017, 91). In addition, Manobo people tend to develop strong family ties with their immediate family members and prefer to stay together in semi-nomadic lifestyle, moving from one place to another within their ancestral land territory, and adhere to the leadership of an elder or tribal leader (Datu) and a spiritual guide (tumanuren). In relation to their realities, Manobo people read it from the perspective of their cosmology and ask intervention from spiritual guardians (tumanud) and from Manama, the supreme God who created the heavens and the earth and everything in the universe.

In Manobo cosmology, the spirit world is considered connected to the physical world and the spirits control the movements of the created order. In this light the unseen world of the spirits is superior and the mortal beings, including the inanimate objects are under the authority and disposition of the spirits. There are two figures within the Manobo culture that bear cosmological functions, namely; the shaman (baylan or tumanuren) and the tribal chieftain. According to Mcmahon who lived among the Manobo in many years, Manobo cosmology with special reference to the world of “spirit beings” which preoccupies the daily lives of Manobo communities and the role of the “tumanuren” who mediates this world to ordinary people, plays an important role in understanding how Manobo cosmology affect their faith and understanding with the character of God in the Bible. All Manobo subgroups in Mindanao share the same spiritual orientation and religious practices (Mcmahon, 2017, 95).

Culturally, spirits are classified into five (groups) namely; supreme spirits (God), the environmental spirits (living on trees, water, cliff, mountains, etc.), the human spirits, the bad spirits (harmful), and the familiar spirits (guardians). All the spirits except the bad spirits are being summoned to come during festivals, farming rituals, celebrations and weddings, food festivals, and welcoming of visitors, and new year thanksgiving. Manama or the supreme God is mentioned first in the prayer as the creator of the heavens and the crafter of the world, then it is followed by summoning the guardians, and other spirits relevant to the occasion that the chieftain is facilitating for. Of course, the prayer ritual is accompanied by betel nut, coins, rice grains, betel herb, and even meat and a live chicken as the spiritual guide to the spirit world. The chieftain would stand before the assembly and holds the chicken (usually a rooster) as he utters his plea and petitions to the gods, then concludes the prayer by slaughtering the chicken and put it on the ground to seek the message of the spirits. If the chicken faces east as it dies then the spirits have answered the petition of the chieftain, but if it faces south then it is a bad omen. When epidemics or people are possessed by evil spirits the intervention of the tumanuren or shaman is needed through a special ritual which is vital to ensure there is established reciprocity between people and spirits and essential to this is the role of the tumanuren. Mcmahon describes the role of the baylan or tumanuren this way, “The baylan is called to the role by the spirits, who, according to Demetrio, wish him or her to act as their intermediary with the world of humans. Invariably a baylan is also viewed as a mediator by fellow Manobo, being in Garvan’s words, the one through whom they transact all their business with the other world. Baylans perform a large proportion of their duties through the aid of their bantoy. Assistance on the part of the latter enables the baylan to analyze the cause of illness in a patient, i.e. what kind of spirit encounter precipitated the malady, where did it occur and what might be an appropriate offering to mollify the offended” diwata (Mcmahon, 2018, p.89).

Culturally, spirits are classified into five (groups) namely; supreme spirits (God), the environmental spirits (living on trees, water, cliff, mountains, etc.), the human spirits, the bad spirits (harmful), and the familiar spirits (guardians). All the spirits except the bad spirits are being summoned to come during festivals, farming rituals, celebrations and weddings, food festivals, and welcoming of visitors, and new year thanksgiving. Manama or the supreme God is mentioned first in the prayer as the creator of the heavens and the crafter of the world, then it is followed by summoning the guardians, and other spirits relevant to the occasion that the chieftain is facilitating for. Of course, the prayer ritual is accompanied by betel nut, coins, rice grains, betel herb, and even meat and a live chicken as the spiritual guide to the spirit world. The chieftain would stand before the assembly and holds the chicken (usually a rooster) as he utters his plea and petitions to the gods, then concludes the prayer by slaughtering the chicken and put it on the ground to seek the message of the spirits. If the chicken faces east as it dies then the spirits have answered the petition of the chieftain, but if it faces south then it is a bad omen. When epidemics or people are possessed by evil spirits the intervention of the tumanuren or shaman is needed through a special ritual which is vital to ensure there is established reciprocity between people and spirits and essential to this is the role of the tumanuren. Mcmahon describes the role of the baylan or tumanuren this way, “The baylan is called to the role by the spirits, who, according to Demetrio, wish him or her to act as their intermediary with the world of humans. Invariably a baylan is also viewed as a mediator by fellow Manobo, being in Garvan’s words, the one through whom they transact all their business with the other world. Baylans perform a large proportion of their duties through the aid of their bantoy. Assistance on the part of the latter enables the baylan to analyze the cause of illness in a patient, i.e. what kind of spirit encounter precipitated the malady, where did it occur and what might be an appropriate offering to mollify the offended” diwata (Mcmahon, 2018, p.89).

Another significant impact of the spirit world among the Manobo is the interconnectedness and continuity of life from mortal being to immortal self. Death bridges the human spirit’s transport from human body to eternity. Once the person dies his spirit would not know he died. Death is like a dreamworld that makes the human spirit experience another reality. The human spirit upon dying hears a rumbling rain coming towards him and so he needs to rush towards the direction with clear sky (rain is believed to be tears of the love ones crying over the dead body), and upon reaching the Talupakan (big and strong tree) he needs put some markings on it by the guidance of the guardian of the tree, then heads towards the big river and crossover (that’s when the dead body turns cold) to Meibulan (guardian of the dead) who welcomes him to Sumulew (eternity). As a general rule, Manobo are afraid of the intrusion of spirits into their world. There is always the risk that spirits will overwhelm humans, an experience that is likely to cause harm and death. For this reason, an individual is usually reluctant to venture into the friendship of a guardian, a process essential to becoming a shaman. To mitigate the casualties, the shaman together with the affected members of the community do some rituals by simply greeting the spirits and make offerings from their harvest and slaughtering a chicken or pig to acknowledge that the supernatural own everything on earth and even control the fate of humanity.

Ethnoscopic: Scriptural lens

The Bible portrays at least two spheres of the world involved in the formation of earth that the humanity inhabited – the spiritual creators and guardians and the physical creation. Throughout the history of the biblical narrative God, as the Spirit, and the Spirit of God were actively engaging the creation. In the process of God creating something the Word is putting flesh on God’s word in order to be tangible and realized (Gen. 1:3,6,9-12,14,20,24,26-27) and the Spirit of God hovered on the water (Gen 1:2) and empowered God’s hero such as Joshua (Num. 27:18), Othniel (Jud. 3:10), Gideon (6:34), Saul (1 Sam. 10:9-10), Samson (Jud. 13:25) and lots of believers in the New Testament that the Holy Spirit was upon them including the twelve disciples of Jesus Christ during the Pentecost and the spoke in other languages (Acts 2:1-13). Another form of spirit that actively engages the created order is the hasatan (Hebrew) or the adversary. There’re the sons of God (Nephilim) marrying the women of humanity (Gen. 6:1-3), the tormenting spirit of God that made the life of Saul difficult (1 Samuel 16:14-23), the accuser hasatan who convinced God to test the faithful man Job (Job 1.6-22), the evil-spirits that possessed and paralyzed some people in the times of Jesus, Paul and the disciples in the New Testament, and even in our generation.

Having these passages in mind, Paul the apostle mentioned among the Ephesian believers to be strong in the Lord and in his might power, to put on the armor of God in order to stand firm against all strategies of the devil (Eph. 6:10-11). On another note, the apocalyptic book of Revelation relates a story about the war in heaven between Michael and his angels against the dragon – the ancient serpent called the devil or Satan, the one deceiving the whole world, and his angels (Rev. 12:7-9). Therefore, the Bible itself shows some facts about the “spirit realm” and the necessity to address spiritual warfare in the line of religious journey of those who have faith in Christ. The denial of biblical narrative about Jesus’ encounter with evil spirits possessing several men, children, and women in the synoptic gospels contribute to the alienation of Manobo cosmology as paradigmatic in the formation of biblical faith by Manobo communities. This negligence of spiritual realm, particularly the “excluded middle” by Western missionaries who lack “spiritual warfare” in their belief system, paralyzed the spiritual journey of Manobo people leading to hollow understanding of God’s power or at worse, abandoning the biblical faith and resort back to their default animism religion they used to practice prior to conversion by the gospel.

Let me cite some passages in the Bible that deal with spiritual encounters and exorcism and how these scenarios contribute to the formation of biblical faith by those people who were directly affected by the incidents and those who have witnessed the spiritual warfare.

1. Jesus drove out a mute demon from the person that caused him to be mute (Luke 11-20).

2. Jesus healed two demon-possessed men in Gadara regions living in the tombs (Matthew 8:28-34). Although a parallel passage in Mark 5:1-20 records one person only instead of two people.

3. Jesus healed the demon-possessed boy that caused him to be in violent convulsion, mouth-foaming, and writhing (Mark 9:14-29; parallel passage in Matthew 17:14-23).

4. Jesus healed Mary Magdalene with seven evil spirits, and she followed him since then. (Luke 8:1-3).

5. In Acts 16:16-34, Paul healed a girl with a demon and the owner of the girl was in rage.

All encounters recorded in the NT show the real existence of the spirits in the world and they disrupt the social order of the human beings by intruding into their community and possessing and tormenting individuals. In response to the crisis, Jesus didn’t ignore the dilemma of the individuals that creates chaos and sufferings of the community. He commanded the demons to come out from the people and restore them into serene state. The effect of his action may vary from place to place as people would succumb to fear of losing material property in place of Jesus or to follow him and abandon their riches and earthly prestige. But definitely Jesus releases them from their suffering.

Another significant biblical narrative that the Manobo worldview can identify is found in 1 Samuel in 28:7-25 as Saul besought the help of prophet Samuel who was long dead in order to be rescued from the fierce Philistine army. Saul asked the woman who can talk to the spirits of the dead to help her awaken Samuel so that he can inquire from him about the will of God. The medium refused to bring up the “ghost of Samuel”, but the king insisted, and she did so. The conversation happened between Saul and the spirit of Samuel, and the outcome was unlikely that resulted to Paul’s devastating breakdown because God departed and left him to die at the hands of the enemies. Why are these biblical passages have been excluded in spiritual trainings?

Ethnoscopic: Missiological lens

The essential missiological approach to the spiritual realm as experienced by Manobo people in Mindanao is best described in the way Jesus deliberately addressed the dilemma of the people which resulted to deliverance from the devilish worldview of the people and transformation of their indigenous faith. Let me identify three factors prevalent in the synoptic gospels that may be worthy of reconsideration for missional pedagogies that we can apply in the context of the Manobo cosmology. First is the manner of Jesus’ deliberate discipleship approach to his proteges who were likely ALFE background. Quoting Webber, Dr. Thigpen says “Jesus is unlike other rabbis in that He does not emphasize memory drills, but a changed disposition in life, in all its habits. A highly relational transfer process similar to that of mentoring, coaching, and sponsoring characterizes the formative trend of this era in contrast to the didactic intellectualized proposition-centered practices after the time of Jesus on earth (Thigpen, 2023, 17). Jesus’ character attracted people to come and follow him, and they learned from him. This is “connected learning” as Jesus relates to his disciples as people that requires human interaction and encouragement. Thigpen notes that the “internalization” is affected by “socialization” (Thigpen, 2016, p. 173). Pragmatic learning comes from experience, observation, participation, reflection and innovations. Jesus opened up to his disciples, stayed and ate with them, washed and fed them, taught them and commissioned them. Research indicates that excellent mentors manifest a general personality tendency in mentoring younger and less experienced people. Johnson and Ridley call this “generative concern” which cannot be taught or trained, but rather, strongly related to “openness, emotional stability, and agreeableness” (Johnson and Ridley, 2008, p. 153).

The essential missiological approach to the spiritual realm as experienced by Manobo people in Mindanao is best described in the way Jesus deliberately addressed the dilemma of the people which resulted to deliverance from the devilish worldview of the people and transformation of their indigenous faith. Let me identify three factors prevalent in the synoptic gospels that may be worthy of reconsideration for missional pedagogies that we can apply in the context of the Manobo cosmology. First is the manner of Jesus’ deliberate discipleship approach to his proteges who were likely ALFE background. Quoting Webber, Dr. Thigpen says “Jesus is unlike other rabbis in that He does not emphasize memory drills, but a changed disposition in life, in all its habits. A highly relational transfer process similar to that of mentoring, coaching, and sponsoring characterizes the formative trend of this era in contrast to the didactic intellectualized proposition-centered practices after the time of Jesus on earth (Thigpen, 2023, 17). Jesus’ character attracted people to come and follow him, and they learned from him. This is “connected learning” as Jesus relates to his disciples as people that requires human interaction and encouragement. Thigpen notes that the “internalization” is affected by “socialization” (Thigpen, 2016, p. 173). Pragmatic learning comes from experience, observation, participation, reflection and innovations. Jesus opened up to his disciples, stayed and ate with them, washed and fed them, taught them and commissioned them. Research indicates that excellent mentors manifest a general personality tendency in mentoring younger and less experienced people. Johnson and Ridley call this “generative concern” which cannot be taught or trained, but rather, strongly related to “openness, emotional stability, and agreeableness” (Johnson and Ridley, 2008, p. 153).

The second concern in teaching-learning is the orientation of the learners. Like most of Jesus’ disciples, most of the Manobo pastors in Mindanao are adult with limited formal education (ALFE) and primarily relying on someone for learning. Like Jesus’ missional methods in teaching his disciples, Manobo pastors also learn from their trusted leaders by way of actual observation and practice, situational inquiry and dialogue, guided activities and mentoring, and praxis. As the teacher contextualize his teaching it makes the gospel incarnational. Simon Chan comments, “The contextualizer of the gospel therefore must have a metacultural framework that enables him or her to translate the biblical message into the cognitive, affective, and evaluative dimensions of another culture” (Chan, 2014, p.11). Metatheological framework is needed because it requires the cooperation of the whole body of Christ, ALFE or literate, in all cultures and through time. In this light the Manobo culture as a member of the international community of churches must internalize their learning through appropriate methods that would facilitate effective and meaningful learning. I like the way Dr. Thigpen rhetorically puts it “How might the lives of millions of adults— masses of ordinary people in everyday life—improve if we make connected learning a priority?” (Thigpen, 2016, p.244). Lastly, the cultural experience of the Manobo pastors seemingly evolving around the Manobo cosmology of the “excluded middle” or considering spirits as superior than the mortal human beings paralyze their understanding of the supremacy of Christ in the Bible. When ecclesial experience excludes the Manobo cosmology in their new spiritual journey with Christ, transformation does not address the cultural DNA of their identity.

Having all this in mind, the relationship between spirit and human is crucial in examining how Manobo Christians interpret Scripture and how they appropriate the character of God and Jesus Christ as supreme spirits in their worldview. This affects also the core elements of an appropriate Christian lifestyle of Manobo when they understand the biblical principles relating to the relationship between the spirits and the people as Christian worldview influences their interpretive process. This experience will give them a new orientation and a new community of faith. In the same manner, Thigpen comments on this matter, “Folk religionists engaged in spiritual patronage understand the potential benefits and obligations of their relationships to spiritual entities. Family and community uphold and perpetuate the system rooted deep in tradition. Therefore, those venturing to leave the familiar middle zone to worship the Creator need a particular kind of discipleship – one involving a system of equally strong support, sturdy roots in a trustworthy God, and clear obligations and rewards – lest those leaving former systems be tempted to return to life on a lesser plane” (Thigpen, 2015, p.2). How do we view the gospel as incarnational, relational, counter-cultural, and transformational?

Ethnoscopic: Educational lens

The importance of this ethnographic study is substantial in the formation of pedagogies that will help the Manobo understand the intent of God in the Bible. Mcmahon argues that this understanding “it runs contrary to missionaries’ normative attitudes towards indigenous cosmologies. The tendency to equate diwata (spirit) with the Christian concept of “demons” means missionaries have usually never considered the possibility that the indigenous spirit domain might possibly shape biblical interpretation. (Mcmahon, 2018, p.100). This folk religion as happening too in Africa elicits the same philosophical question, “Why do Bobo Christians revert back to their ancestral religious practices?” He was told, “As older Bobo Christians sense the end of their life approaching, they feel more and more distant from Christ, and they feel closer to their ancestors. They return to the religions of their ancestors because they know the ancestors through kinship bonds. They do not know Jesus that way.” (Thigpen, 2015, 20). Now how do we address the issue of Manobo’s fear of evil spirits and Christological gap for eternity? What can we learn from the previous methodologies employed by missionaries? Since the 1970’s Manobo communities had been reached out by General Baptist American missionaries together with Overseas Missionary Fellowship (OMF) using a linear, systematic, and print-based pedagogies. The approach was one-sided and oppressive since dialogue, collaboration, and cooperative learning were not encouraged. Moreover, Manobo worldview was not explored as prerequisite to formation of curriculum particularly on the spirit world.

A paradigm shifts in presenting the gospel through ethnoscopical method will address the core of the spirit world in the Manobo worldview. Here’s the outline of the potential narratives in the Bible that will address Manobo cosmology:

1. Spirits exist and challenge God’s authority. (Hasatan – Job 1)

2. Jesus encounters demon-possessed individuals

a. Jesus drove out a mute demon from the person that caused him to be mute (Luke 11-20).

b. Jesus healed two demon-possessed men in Gadara regions living in the tombs (Matthew 8:28-34). Although a parallel passage in Mark 5:1-20 records one person only instead of two people.

c. Jesus healed the demon-possessed boy that caused him to be in violent convulsion, mouth-foaming, and writhing (Mark 9:14-29; parallel passage in Matthew 1:14-23).

d. Jesus healed Mary Magdalene with seven evil spirits, and she followed him since then. (Luke 8:1-3).

e. In Acts 16:16-34, Paul healed a girl with a demon and the owner of the girl was in rage.

3. ANE Medium to the spirit world (1 Samuel 28:7-25)

4. Christ as the medium of God’s ultimate sacrifice for the trespasses of human beings (Hebrews 10:1-18)

5. The supremacy of Christ over all creation and the restoration of the relationships through him as an incarnated God. (Book of Colossians).

6. Jesus Christ as way to eternity (John 3:1-21).

7. Grand narrative of God creating the universe, the spirits, and the final kingdom to be unfolded.

Inclusive community of believers who pray for one another, study and reflect on God’s story, practice spiritual formations and disciplines, learn and grow together by addressing the cultural challenges, and missional church play an important role in making the gospel contagious to other people. The aim is making the gospel decolonized, cross-cultural and culture transforming, incarnational and relational than systematic, didactic, and cognitive processing of discipleship. In the experiential encounter with the Holy Spirit as part of prayer training in spiritual warfare, a certain pastor who was converted into Christianity in a very uncommon way started a prayer movement in his village with a specific place to pray and fast. He has been hosting prayer meetings, deliverance, and encounter with the Holy Spirit which effectively attested the supremacy of the Triune God over the evil spirits. We invite him constantly to our gatherings and we participate with him in prayer meetings.

Alongside mental training and spiritual formation and discipline comes the artistic expression of worship that is meaningfully and culturally relevant for the people. Rituals are necessary elements of expressing worship to the creator evidenced by biblical characters and the artistic artforms that Manobo culture exhibited in their festivals and gatherings even before Christianity became known to them. Manobo worshippers may not be able to appreciate the essence of their existence if certain artforms are not welcomed in community services. Ethnoarts is a ministry that could facilitate a deeper appreciation of Manobo culture in line with God’s artistic gifts to mankind, critical understanding of the relevance of using artforms in worship, and critical reflection and wisdom in appropriating cultural artforms in worshiping God. The manners which Manobo people be able to process, retain, and pass on information will be through songs, oral arts, dance, music, food, visual arts, and language.

Conclusion

As a general rule, Manobo people are afraid of the intrusion of spirits into their world and may overwhelm the human that will result in fatal blow. As a result, they need to appease the spirits through sacrifices, becoming a shaman or medium which in return the spirit would ultimately to take its human companion back to the spirit world as a payment for his intervention. Moreover, the power of family connection and spirit-world embedded in the culture of Manobo passed on orally from generation to generation become a reality to them which suffocates their faith in Christ in times of trials and hardships.

Looking at the biblical account in the first century Christianity one can therefore identify with the existence, attributes, and societal dilemma effected by the spirit world to humanity as universal phenomenon or at least a fraction of the world controlled by it. Those few encounters of Jesus alone in the NT would give us a missional perspective concerning the pedagogies that we can employ in contexts similar to what the disciples have witnessed as they learned practical approaches to dealing with spirits. Like the disciples, Manobo pastors leading their respective communities without proper training concerning the tension between the “excluded middle” and monotheistic religion introduced to them by those experts of excluded religion employing print-and-knowledge based learning, systematic and banking education, and colonized gospel. For the most part, Manobo culture is ritualistic and socially oriented, and it values communal enterprise. It is shaped by the world of spirits and the identification with Christ as a distant god could not compare to the harmful acts of evil-spirits to them since time immemorial. However, in Colossians, Paul emphasized the supremacy of Christ promises love, hope, freedom and deliverance (Colossians). Quoting Isaiah 61:1-2, Jesus purposely read the prophetic words of God in the public,

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Then he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant and sat down. The eyes of everyone in the synagogue were fastened on him. He began by saying to them, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.” (Luke 4:18-21).

May we learn from the Master-artist in his paradigms in dealing with cultures struggling with the casualties of the “excluded middle” by fasting and prayer, exorcism, intimate and intentional discipleship through ethnoarts, orality training, narratology, and learning from individuals/shamans whom God delivered from spiritual bondage, and above all things, having an encounter with the Triune God in his spiritual realm.

The Writer

Mr. Tano “Likalik” M. Emboc

Executive Director, Ethnoarts Philippines, Inc. | Jesus Film Consultant | Bible Translation Specialist | Indigenous Missiologist

Mr. Tano Emboc is a highly experienced indigenous missiologist, Bible translation specialist, and cultural transformation advocate serving as the Executive Director of Ethnoarts Philippines, Inc. A member of the Manobo tribe from Mindanao, he has committed nearly two decades to advancing contextualized ministry and discipleship among indigenous communities across the Philippines.

Mr. Emboc began his work in 2005 as a Mother Tongue Bible Translator, and over the years, he has served in several strategic roles, including:

• Translation Coordinator for Wycliffe Philippines (2013–2016)

• Language-Level Translation Consultant (2014–present)

• Ethnoarts Coordinator (2014–present)

• Consultant for Oral Bible Storying (2015–present)

• Trainer and Workshop Facilitator in Scripture translation and discipleship

• Board Member of Matigsalug Language Christian Association Inc. (2014–present)

He also worked as Deployment Manager for Wycliffe Philippines (2017–2018) and currently serves as a Facilitator and Consultant with the Jesus Film Project (2019–present), helping indigenous communities experience Scripture and the gospel in visual and oral formats that are both powerful and culturally resonant.

Mr. Emboc has received extensive training in discourse analysis, translation consulting, oral Bible storytelling, and exegetical methods—having attended consultant development workshops in the Philippines and India, as well as numerous Jesus Film trainings.

He holds a Bachelor of Elementary Education from Holy Child School of Davao (2010), a Master of Divinity in Biblical Studies from Asian Theological Seminary (2014), and is currently pursuing a PhD in Bible Translation and Technology (2022–2026), further strengthening his commitment to innovative and accessible Scripture engagement among marginalized peoples.

With a passion for indigenous leadership development, Mr. Emboc works to equip adult learners—especially those with limited formal education—through relational and incarnational models of discipleship. His work embodies a decolonized, transformative approach to missions, where the gospel engages culture not to erase it, but to renew it in Christ.

Bibliography

Thigpen, L. (2020). Connected Learning: How Adults with Limited Formal Education Learn. (American Society of Missiology Monograph series, vol.44). Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications.

Bartholomew, C. G., & Goheen, M. W. (2013). Christian philosophy : A systematic and narrative introduction. Baker Academic. Created from liberty on 2023-03-04 23:39:46.

Wickett, R.E.Y. (1991). Models of Adult Religious Education Practice. Religious Education Press Birmingham, Alabama.

Johnson W. & Ridley C. (2008). Elements of Mentoring. USA: palgrave macmillan.

Freire, P. (2007). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: The Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd.

Chan, S. (2013). Contemporary Ethics. Philippines: National Book Store Inc.

Chiang, S. & Lovejoy G. (2013). Beyond Literate Western Models: Contextualizing Theological Education in Oral Contexts. Hongkong: International Orality Network.

Thigpen, L. (2020).Deconstructing Oral Learning: The Latest Research

(journal)

Thigpen, L. (2015).AN EMIC UNDERSTANDING OF THE “EXCLUDED MIDDLE”: SPIRITUAL PATRONAGE IN CAMBODIA. (journal)

Thigpen, L. (2023). When Signature Pedagogies Clash: Making Way for the Oral Majority. (Journal)

Knight, G. (2006). Philosophy and Education. USA: Andrews University Press.

Mcmahon, W. (2017). An analysis of the reception and appropriation of the Bible by Manobo Christians in Central Mindanao, Philippines. University of Edinburgh Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation.

Or Download the PDF version here… https://ethnoartsphilippines.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/exploring-the-excluded-middle-of-manobo-cosmology-for-relevant-and-transforming-pedagogies-among-manobo-christian-leaders-of-mindanao-philippines-repaired.pdf